What's Best About America (& Why I'm Worried)

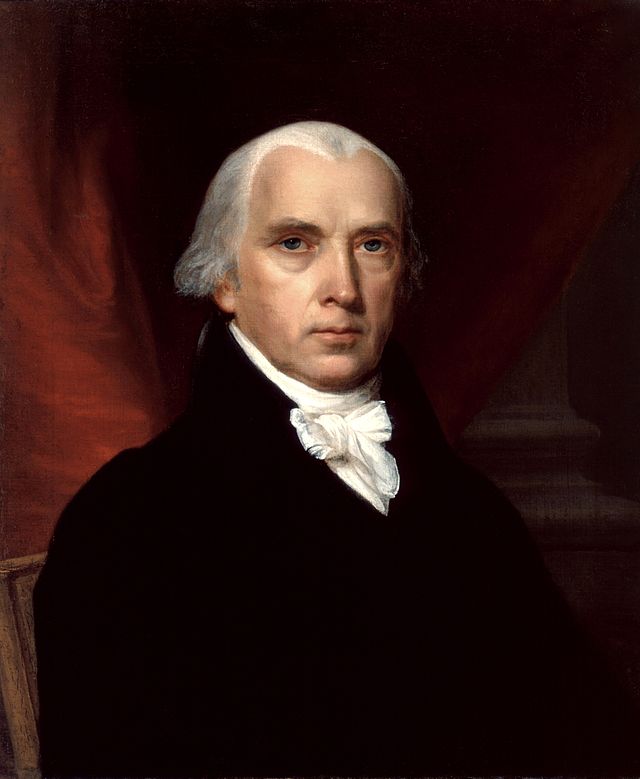

(The crowd really gets going at the "rockets' red glare" part, about 33 seconds in--makes my hair stand up. USA!)[7/8/14 update at 9:36 AM CDT: I've slightly edited the post for clarity.]The Framers of the American Constitution had a deeply-held belief in human sin. That clear-eyed expectation of sin?particularly the expectation that anyone is capable of using power in oppressive ways, and that given time and opportunity, anyone probably will use power in oppressive ways?is what I like best about America. James Madison, writing in 1788 in?The Federalist #51 under the pseudonym "Publius," had this to say about the underlying philosophy of the America Constitution:

James Madison, writing in 1788 in?The Federalist #51 under the pseudonym "Publius," had this to say about the underlying philosophy of the America Constitution:

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

Madison and the other framers of the Constitution were so aware of the human capacity for sin that they set up a system of checks and balances to limit sin's effects, so that power couldn't be too closely-held in any one set of sinful hands. Madison didn‘t merely want to keep permanent power away from his political enemies, he also wanted to keep permanent power away from his political allies. Madison was aware that his ideological allies were as likely to fall into sin as his ideological opponents. So, Madison and the Framers built a permanent mistrust of human nature into the American Constitution. This brilliant design has served us well for the last 200 years or so. We've had a lot of problems, but not anarchy and not tyranny.The best thing about America is the wisdom our Founders had to recognize that humans are deeply sinful creatures.? This insight of human sinfulness is, surprisingly, not universally acknowledged. 100 years ago, for example, many intelligent, educated people in the West believed that humans were on a path towards perfection. And then came the Somme.Sin is a part of every human life, and every human situation. We cannot perfect ourselves, cannot trust our best intentions. All of us, even the best-intentioned, are capable of acts of great evil. In the past 200 years, there have been countless revolutionary movements that promised freedom and justice, and a great number of them have made things worse for ordinary people rather than better. The reason revolutionary reality is so much worse that revolutionary rhetoric is because the leaders of these revolutions had no suspicion of their own intentions, no awareness that their hearts were often no more holy than the enemies they wanted to overthrow.In America, this was not the case. James Madison??if men were angels??knew that men and women were far from angelic, and he and the Framers took the human capacity for sin into account as they drew up our Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Why I'm Worried

But I'm worried today that we've forgotten what we once knew. Today what most worries me about America is that many of us no longer believe in the universality and inevitability of human sin in all situations and in all lives.Don't misunderstand: it's not that we no longer believe in sin in general; rather, it's that we don't believe in the universality of sin; we no longer believe that?we ourselves and our people could be sinful in our actions.The American Left--particularly the progressive wing--seems only to see sin where it wants to see it.? The Left is quick to see possibilities for sin in for-profit corporations, among the rich, or in cultural systems that have in the past been used to oppress the weak. The Left is correct to see the possibilities for sin in these areas.But the Left seems blind to the possibilities for sin among government bureaucracies, among the poor, or in the progressive push to completely dismantle so-called traditional morality. The Left also seems unable to question its own crusading impulse, unable to concede that perhaps it could be mistaken in its inclinations. This is an extremely dangerous inability.To cite one recent example: The Left correctly complains that much of right-wing rhetoric about President Obama is hysterical and vitriolic. But the Left‘s response to the Supreme Court‘s Hobby Lobby case has itself been hysterical and vitriolic. Steve Coll, writing for The New Yorker‘s website, compared the Green family (the owners of Hobby Lobby) to the Taliban. I had to read the article twice to be sure he wasn‘t making a joke. Unfortunately, he appears to be in earnest; Mr. Coll also appears to be unable to see the sad irony in his use of the comparison.The American Left could use more of Madison‘s clear-eyed view of human sin. The men and women on the Left should be aware that they are as capable of using power in oppressive ways as anyone else.But my conservative readers should not be feeling too good about themselves, either. The American Right also seems only to see sin where it wants to see it. The Right is quick to see possibilities for sin among government bureaucracies, among the poor, or in the progressive push to dismantle traditional morality. The Right is correct to see the possibilities for sin in these areas.But the Right seems blind to the possibilities for sin in capitalist structures, among the wealthy, or in its media-entertainment complex. And the Right seems rarely to apply it's criticism of the Left to itself.The Right often accuses the Left of being out-of-touch with reality, unable to see the hard truths about the inevitability of sin in all human endeavors, that the Left is naively idealistic. But, the Right is capable of making the same mistakes and ignoring Madison's wisdom. To cite the clearest example of the last decade, consider the Iraq War and occupation. The leaders and planners of the war and subsequent occupation suggested that it would be relatively simple and inexpensive to remake Iraqi society. I have a hard time believing Madison would have been so sanguine. A healthy skepticism of human intentions--particularly with regard to human use of political power--and an abiding belief in the pervasiveness of human sin should have caused the architects of the Iraq War to expect more more difficulty when they laid out their plans. For example, a Madisonian understanding of the human use of power to oppress should have given the Iraq War architects the expectation that the leaders in the new Iraq would use violence against their political enemies in the same way that Saddam Hussein had formerly used it against them. Unfortunately--and I am of course only speaking as an outsider--these war architects seem to have ignored Madison's insight, with predictable results. When you forget about the inevitability of human sin and forget that you are capable of making the same mistakes that you have accused your opponents of making, you inevitably find yourself in a mess.

What the Left and the Right Share in Common

Here's the point: both the Left and the Right are capable of committing the sins that they have accused each other of making. (I know that's an obvious point, but I often find it helpful to point out the obvious.) I'm not arguing for some kind of middle or third way or saying that there is no substantial difference between the Left and the Right in American life. Rather, I'm just pointing out that a more Madisonian skepticism of our own righteousness would be beneficial for each of us, and for our ideological allies. The reason both the Left and the Right are capable of making the same mistakes is because they forget about the human capacity for sin, at least in regard to their own ideas and leaders. Both, in their own ways, believe that their ideas and practices can lead us toward perfection, that their desires are pure enough to be exempt from tendencies to self-delusion and abuses of power, and that the purity and righteousness of their desires justify any means to achieve those desires. This shared belief in their own righteousness?one of the things they have in common?is foolish and, I?d argue, un-American. And it causes me to worry. So, what should we do?

Two Things I'm Going to Do More Of

I?d like to see two changes in American public life. But, as with all changes, these must begin with each of us. I have control over no one‘s behavior but my own, just as you have no control over anyone but you. So, I want to see more of these two things in my own life:First, we need to remind ourselves that, to quote scripture, all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. In other words, no one is perfect, and no one‘s motives are perfectly pure. Each of us is capable of abusing power and justifying lies for our own, selfish ends. There but for the grace of God go I. I am no better than my enemies. I want to be reminded often of this sobering truth.The Christian practice of confession is valuable because it is impossible to pray a corporate prayer of confession and fail to hear the words applied to yourself. In my tradition, for example, we have a prayer of confession that goes like this:

Merciful God, We confess that we have not loved you with our whole heart. We have failed to be an obedient church. We have not done your will, we have broken your law, We have rebelled against your love, We have not loved our neighbors, And we have not heard the cry of the needy.

Every time I pray those words, I know that they apply to me: I am a sinner. I judge myself by my intentions but my enemies by their actions. In times of honesty and silence, I am forced to admit that I am not better than my enemies.Second, we need to confess our own sin and admit when our people have sinned. We cannot condemn the dirty tricks of our political and ideological enemies while turning a blind eye to those of our own people, whom we want to believe justified in their actions because we believe their ends to be so righteous. It would be powerful to hear people say, Yes, I voted for him, and yes, I broadly agree with his position on X issue, but he was dead wrong in how he spoke about his political enemies, and dead wrong to pursue power in that way, and I don‘t want to win if that‘s the way victory is achieved. I'd like to demonstrate more of this admission and honesty in my own life.What I like best about America is our Constitution‘s undergirding suspicion of power, even when used by seemingly good people. That suspicion has served us well for the last 200 years, and has kept us safe. We ignore that suspicion at our peril, but if we recover it in our own lives, our families, and in our public life together, it has the potential to keep us safe in the future.

?The Framers were not exempt from the temptation to ignore their own tendencies to sin, and the inclusion of slavery in the Constitution proved..?I am not suggesting that the current Iraqi government is as violent or oppressive as that under Saddam Hussein, but merely making the point that the years of sectarian violence that have followed Saddam Hussein's overthrow should not surprise us.